I have so many other things I’ve been meaning to post (reviews of the concert experiences I’ve had in the past year, my summer lookback post, or continuing any of the series I’ve already started), but I woke up one morning and thought “I have to write something gay today”, so here’s the result. I’m not just starting series left and right without any intentionality, by the way: these have all been in my head as ideas before I even created this Substack, I’m just introducing them gradually, as time and creative energy allow. I fully intend to continue each and every one of them, with 10-15 ideas already lined up; this is just sadly not my full-time job!

What is this series?

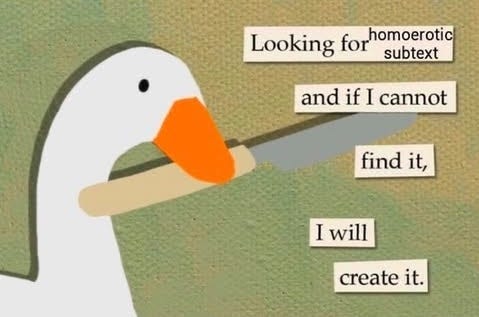

The name already speaks for itself: Queer subtext exploration, which will see me harvesting all the queer subtext that’s already there in kpop, ripe for the taking. With that being said, this meme was also one of my main inspirations and will be my guiding light throughout this journey:

I do believe that most art can be read through a queer lens and can be queered, even if that was not the original intention. There is a whole school of thought in the philosophy of art (which I happen to have majored in besides English literature and art history) that says meaning can be or should be separated from what the artist intended it to be, and the spectator/listener/etc. is an active participant in the creation of the art piece by adding their own meaning. Just to name a few, Roland Barthes argued in his work Death of the Author, that once a text is released, the author’s intention becomes irrelevant, and meaning is created by the reader. According to Hans-Robert Jauss, a key thinker in reception theory, meaning evolves over time and is not fixed by authorial intent. Umberto Eco saw the audience as co-creators, completing the work’s meaning through their own perspective. These theories all open the door for queer readings.

You might think that this is an overly scholarly introduction to a series where I will basically debate why certain kpop songs are gay, but my favorite genre has always been applying the fancy academic knowledge I’ve acquired in school to subjects that are traditionally considered low-brow or unserious, like pop music. Also, I had to drop some big names, so if any combative cishet reader happens to read this and wants to argue about whether it’s okay to see gay things where they might not be, I can just shut them up by pointing them to these authors.

There are also a few disclaimers I feel like I need to make. I’m not claiming that my interpretation reflects the intention of the lyricists, choreographers, or even the artists themselves; mine is just ONE interpretation, that happens to be a queer one. We, queer people, are allowed to take up space, interpret art according to our own desires, and share our findings with the world. Obviously, if you disagree, this space isn’t for you.

Secondly, even if I talk about eroticism among members of a group, you don’t have to assume it’s in a shipping context. Don’t get me wrong, I do ship some idols romantically, and I’m not afraid to admit to that, even though it’s basically taboo and we’re actively being demonized in the kpop fandom. However, this content is about analyzing lyrics, choreography, visuals, and music in search of possibly queer meaning, not proving that certain idols might be into each other. If you want to read it through a shipping lens, that’s completely fine by me, and if you want to imagine that the idols perform these songs (and perform them so well) because they’re queer themselves, that’s also valid. I’m not stating either of these things as facts, even though all possibilities are always on the table. For those who prefer more distance, you can consider these songs and performances as theatrical exercises, as so much of kpop actually is, that happen to depict queer stories and experiences, at least according to my reading.

And one more, final note: the code and symbolism of queerness is markedly different in Korea than what those of us growing up exposed to Eurocentric media are used to. What I’m doing in this essay and how I perceive queerness is inevitably informed by my living in Europe, so rather than actual commentary on Korean culture and queer representation there, take this as a fun experiment in literary analysis, one that brought me a lot of joy in dark times.

Now, let’s put all my hermeneutics classes to good use and dive deep into why Kill the Romeo by ZEROBASEONE is a gay ass song! ✨

Song introduction and background

To start out, here’s Kill the Romeo, the song, and the best performance of it that I’ll be referencing throughout this analysis:

The story the song tells is pretty simple: the speaker (presumably male since male idols perform the song) evokes the premise and setting of Romeo and Juliet and thus conveys that this is also a tale of star-crossed lovers who are bound to meet a tragic end. However, instead of accepting this predetermined fate and the sad ending, he takes control of their destiny, flips the script, and becomes his own person instead of taking on the role of Romeo. The two escape what is written for them and what is expected of them, and write their own narrative, one that ends happily.

This is pretty neutral so far. Since there are no gendered expressions anywhere in the lyrics, it could easily lend itself to either gay or heterosexual explanations. However, while Romeo’s name is mentioned exactly nine times, in seemingly vague ways that make us question who Romeo is (the speaker? the person he’s talking to? a role he rejects?), there is zero mention of Juliet or any feminine descriptors.

I can’t skirt around the topic of how Western kpop fandom circles just seem to have accepted that ZB1 is a gay group, that’s their image, they’re for the gays. Almost all the members had some sort of queer-adjacent side quests in their pre-idol lives, the group is home to one of the most popular kpop ships of all time, and they were formed in the most gay-coded of all survival shows, Boys Planet (season one), where many of the contestants who didn’t make it to ZB1 went on to debut with genderless or otherwise boundary-pushing concepts. ZB1 themselves have embraced this image, and are the 5th-gen kings of gay fan service. Whether that behavior is genuine or not is a topic for another day, but I want to establish one of my core beliefs here, namely that queerbaiting doesn’t exist when we’re talking about real people. You will never know why someone embraces queer fan service, and pressuring them to come clean or dismissing all of it as a charade are both deeply queerphobic. So let’s just take all of the above as the facts that they are, and consider them when thinking about whether a gay interpretation of Kill the Romeo might be far-fetched.

However, even if none of the above comes into play, I can still make my own meaning, and to me, this is a narrative of a gay person in love rebelling against the constraints society puts on queer relationships and deciding to make their own destiny instead of the prescribed and expected tragic one. It is also an expression of queer joy and self-determination in the face of prejudice.

Key queer/homoerotic themes

Here are the main queer and homoerotic themes that stood out to me, that shaped how I read both the song and its performance:

The phrase “Kill the Romeo” is a rejection of heteronormativity

Romeo is the ultimate heteronormative romantic hero, and killing him implies rejecting that traditional role and possibly rewriting the script to allow a different kind of love.

Forbidden love, us against the world

The lyrics echo classic queer narratives of forbidden love and the need to fight against society’s judgment.

Theatrical metaphors

The description of the initial setting and references to “Act I” and “Act II” establish this as a performance, one where the protagonists are self-aware and know they are playing a role or at least expected to. However, instead of passively acting out a love story, they exercise agency to change the script.

Forging your own destiny and rebelling against a fate laid out for you

Taking control of one's own path, not what society dictates, is the most ubiquitous theme in the lyrics. It also directly subverts the classic Romeo and Juliet narrative, and that opens up the interpretation for queer love, which is also often depicted as doomed love.

Queer liberation trope

Escape and liberation are common themes in queer literature. Leaving a hostile world for one where love is allowed and free, creating a safe haven to be alone together, is the greatest and most enduring queer fantasy.

The performance

The choreography balances between intimate and intense, and has a central scene where proximity and touch between two men tell a very clear story.

Close reading

There’s nothing else left to do than go through the lyrics line by line and examine their symbolism. As usual, I left out the lines and filler words that do not contribute to the analysis. The credits for the translated lyrics go to Genius Lyrics and Zaty Farhani on YouTube. I went with whichever version of the translation was better for each line.

The time we’ve been waiting for, time to wake up

Open the window bathed in moonlight

Our excited gazes meet,

You and I, we believe in this moment

"Time to wake up", to me, suggests an awakening of self (or perhaps one’s discovering their own queer identity) in this context, and readiness to act. The “we” implies that both the speaker and his love interest experience the same feelings.

Moonlight (while also evoking the popular balcony scene in Romeo and Juliet’s story) here is sensual, secretive, traditionally linked to nighttime romance, often used in queer-coded imagery where love has to exist in the dark and on the margins.

"설레는 눈빛이 마주쳐" (eyes meeting in excitement) can be read as a mutual, possibly forbidden desire. The moment is about ‘you and I’, the outside world is not involved in this scene. The gaze described here is intimate and equal; it’s not just a one-sided pursuit but a shared yearning.

We do it like Act One

The reference to Act One of Romeo and Juliet is particularly loaded, since this is the moment where the pair’s love first blooms in secret. Romeo and Juliet meet for the first time at a masquerade ball. In a queer context, this evokes the feeling of falling in love in secret, in a world where your love isn’t accepted, and having to mask your true self. Their instant connection defies social norms and family expectations. The "we do it like Act One" line can thus mean that the speaker and the person he addresses are also meeting under impossible circumstances, in secret, knowing they will have to fight for what they have.

One day, like a twist of fate

The moment I first saw you, I knew for sure

Even if I'm the main character in some tragеdy, I’ll promise you

I'll change everything tonight

In my queer reading, I see “twist of fate” as recognizing love in an unexpected person. While in the classic drama, it means falling in love with a person from the rival family, here it perhaps refers to someone of the same gender, which similarly upends the traditional script.

The line “even if I’m the main character in some tragedy” is one of the most crucial when it comes to the message. Queer love stories have been historically burdened with tragic endings, erasure, or social punishment, and I feel like this line is an acknowledgment of that fact, as the speaker recognizes it in his own story. But this is also where the lyrics first see the protagonist vow to defy that fate.

Baby let’s kill the Romeo, flip the destiny

It falls like dominos,

No, it’s not a tragedy

Forget the Romeo,

I’ll decide with my own hands the path I’ll walk on

As I already pointed out, Romeo is an archetype of heterosexual love, the tragic male lover. Here, killing Romeo is symbolic of rejecting heteronormative tragedy.

"뒤집힌 destiny" (reversed/flipped destiny) is another key phrase, and it signals taking control of one's own fate, not following a predetermined path (as he explicitly says so in the last line of this section).

The “it’s not a tragedy” line reiterates that he refuses the sad ending.

We can be runaways,

Just the two of us slip away,

All I need is you, the ending we write will be different

We can be runaways,

Sadness will fade away

A new Romeo just for you, I’m going my way

I already identified escape as an essential queer narrative trope, and this is the part of the song that establishes this as an option.

“우리가 쓸 엔딩” (the ending we write) is reclaiming authorship over their story, another powerful metaphor for queer autonomy.

“A new Romeo just for you” can suggest creating a new kind of romantic partner, outside the standard cliché of a male hero + a female love interest. This line could also be hiding a reference to same-gender romance: the speaker becomes “your” Romeo, tailor-made specifically for the love interest, but different from the traditional image that lives in the listener’s mind. It’s a very covert reference, but to me, it certainly invokes this kind of image.

No cliché, the unexpected Act Two becomes our story

Oh wait, let’s change the genre, continue to the next page

You and I are protagonists on this stage

“No cliché” supports my explanation of the previous part: the characters in this play refuse predictable, heteronormative romance tropes.

In the referenced Act Two of Romeo and Juliet, they profess their love for each other and get married, defying the rules of the world they live in. The queer narrative follows so far, but the next lines explain how their story diverges.

"Change the genre" could literally mean redefining the type of love story, from tragic to joyful, but it could also mean from straight to queer, or from hidden to open. The line “You and I are protagonists on this stage” further upholds the song’s message of taking your fate into your own hands, and is, in my opinion, the core of the whole lyrics and story.

Notably, this is the lyrics sung at the point in the choreo that inspired me to start exploring this queer interpretation in the first place. See my analysis of the key choreography part in the “Performance” section!

I don’t love it, a predetermined fate

I don’t love it, the idea that we can’t be together

It’s too late to turn back now, before the moon sets

I’ll change everything tonight

This is a direct protest against societal rules that say the two can't be together. These lines reflect the internal and external battles queer people face in situations where love can’t be freely expressed.

“It’s too late to turn back now” is an acknowledgement of the fact that once awakened, queer identity and love can’t be hidden and repressed again.

“Before the moon sets” indicates urgency that the escape needs to happen under the cover of the night. It can also symbolize a window of freedom, a fleeting moment to love each other, before they must return to society and all of its constraints.

Now let’s leave this place, you and I will write a new story

Beyond the broken moonlight, in a world that’s just ours

The moment we dreamed of is right before us

"A world for just us" is the classic queer fantasy of a private, safe world, one “beyond the broken moonlight”, which stands for a harsh reality.

The line “the moment we dreamed of is right before us” shows that the desired ending is finally not that far, and it’s within arm’s reach.

Fly high, I take control,

This is our story,

You better get out of my way,

Kill the Romeo

“I take control” reaffirms the main character’s agency, and “get out of my way” expresses his defiance.

The last “Kill the Romeo” here is emphatic and empowering, the final act of destroying the limiting myth.

We can be runaways,

Dancing the night away

With this part, we finally reach the joyous release, celebrating love. The instrumentation also turns more festive at this point.

Romeo I’m going my way

The brilliancy of this closing line lies in how open to interpretation it is. Without punctuation, we get multiple layers of possible meanings.

And that leads us to the question:

So who IS Romeo?

Some possible interpretations:

“Romeo I’m going my way” could mean he is addressing Romeo as the love interest, and the rest of the sentence refers to his own breaking away from the mold he is expected to fill. However, this version doesn’t explain the whole killing thing, so we can assume Romeo is not the love interest.

Or he’s telling Romeo, “I’m choosing my own path, away from you,” the ‘you’ here being this ideal man that the expectations and pressures of society want him to become.

If the speaker himself is Romeo, this could be a rejection of the archetype:

“Romeo I’m going my way” means he’s no longer playing this role and leaving it behind.

The sentence, in this case, symbolizes self-liberation from the tragedy, toxic masculinity, and compulsory heterosexuality.

I would say the second and third interpretations complete each other, and can be true simultaneously.

Performance

Admittedly, my turf is literature and texts in general, so I’m sure my thoughts on the choreography will leave a lot to be desired, but there are a few things I really wanted to talk about.

I’m not that delusional, so I’ll readily admit that there isn’t much in the choreography that supports my theory, apart from that one key scene between Gunwook and Jiwoong, the part that actually triggered the writing of this whole piece. Without exaggeration, I’ve watched that part thousands of times, and sometimes I wake up in a cold sweat thinking about how gay it is. There are a lot of choreographies and lyrics in kpop that are more explicitly homoerotic. Still, to me, this one reigns superior over even “tame me” and simulated dick grabs (iykyk).

Below, you can find two videos (both under ten seconds), personally cut by me, to illustrate my point:

(Credits to Studio Choom and Mnet)

The tension, the story the body lines tell, the eye fucking, and the suggestiveness make it more impactful than anything more explicit I’ve seen in the genre. It also helps that Jiwoong and Gunwook are amazing performers who manage to embody desire in such a tangible way that I can almost feel it on my skin. And last but not least, one of these men is an established BL actor who is proud of his work, and the other just said a few weeks ago that he likes both women and men who like him. None of this automatically means that they’re gay (or gay for each other), but they both have connections to queerness that make their performance more meaningful for queer fans.

The reason I think this part is the core of the performance is due to the lyrics mentioned above (“let’s change the genre, continue to the next page/You and I are protagonists on this stage). These lines, paired with that choreography, don’t actually leave too much to the imagination, and when you look at the two together, it doesn’t seem like a huge stretch to be looking for a gay meaning. People also often mention how this is Gunwook and Jiwoong’s song, even if they didn’t get the most parts according to the line distribution. They seem to have embodied the concept the best, and they DO seem like the two protagonists, not just based on this part, but the two of them did get all the most impactful parts of the choreography. Gunwook is the center at the beginning and end of the song and during one of the choruses, plus he is one half of the couple choreo I am referencing, while Jiwoong has memorable lines in the chorus, bridge, and participates in the couple choreo.

Closing thoughts

Is Kill the Romeo gay? I’ll let every reader decide for themselves. It’s obviously a song about a forbidden love, but what makes that love forbidden is up for discussion, in my opinion.

The official visualizer and the intro to the MAMA performance did reference a female love interest, which I wanted to mention for the sake of objectivity (though I’d argue against the latter because even though Juliet’s name is said out loud, there is still no woman in sight, only men, men, men everywhere). Thus, it’s clear that the company didn’t mean to market this as a gay song, but that’s far from surprising. The kpop industry is guilty of promoting and benefiting from homosexual imagery or ambiguity when it comes to queer topics, while not openly supporting or standing up for LGBTQ+ people. But that will never stop us from making our own meanings and interpretations, whether they’re encouraged by the creators, the companies, or even the rest of the fandom.

And last but not least: how was this?? I have to admit, I haven’t had this much fun writing anything I’ve published here. I really miss being a literature student and writing essays full-time, so this let me tap into that part of myself again and remember how much I love digging deeper into art and pop culture.

Let me know what you thought and if you’d be interested in reading a similar analysis about other songs! You can even give suggestions, and I’ll see what I can do 🤭

Reka I loved reading this!!!! Really interesting! I wish I had your education and sense for words. And the part that you showed in the two clips, they perform it so well, the desire and all clearly visible. Thank you for writing this essay. And I'm really glad you had fun writing!